Essay

Activating from Rest and Resting from Activation

by Verana Codina

"El universo se encogió en madejas fantasmales" at La Nao, curated by Fabiola Iza

Reading time

5 min

Embroidering, weaving, darning, and sewing are practices—normally associated with “femininity,” domesticity, and the realm of the amateur—that are often relegated to mere eventualities. El universo se encogió en madejas fantasmales [The Universe Shrunk into Ghostly Skeins] brings together works in which the act of weaving or embroidering is a vehicle for enunciation and political emancipation. Whether from desolation or pride, the featured artists enunciate and denounce narratives that have conditioned them as subordinate, passive, and inert subjects, rendering them diligent, active, and energetic: in short, alive.

This coming-and-going between rest and activation is exposed not only in the pieces, but also in the historical resistance that women have demonstrated before an eternally patriarchal world. Both concepts come from notions of time; they are terms suggesting its stoppage or its impetus. Let’s say that, in the context of the exhibition, resting means inhabiting domestic space, while activation means disturbing the public one. This does not, however, mean that both relationships are exclusive; rather, they are interchangeable.

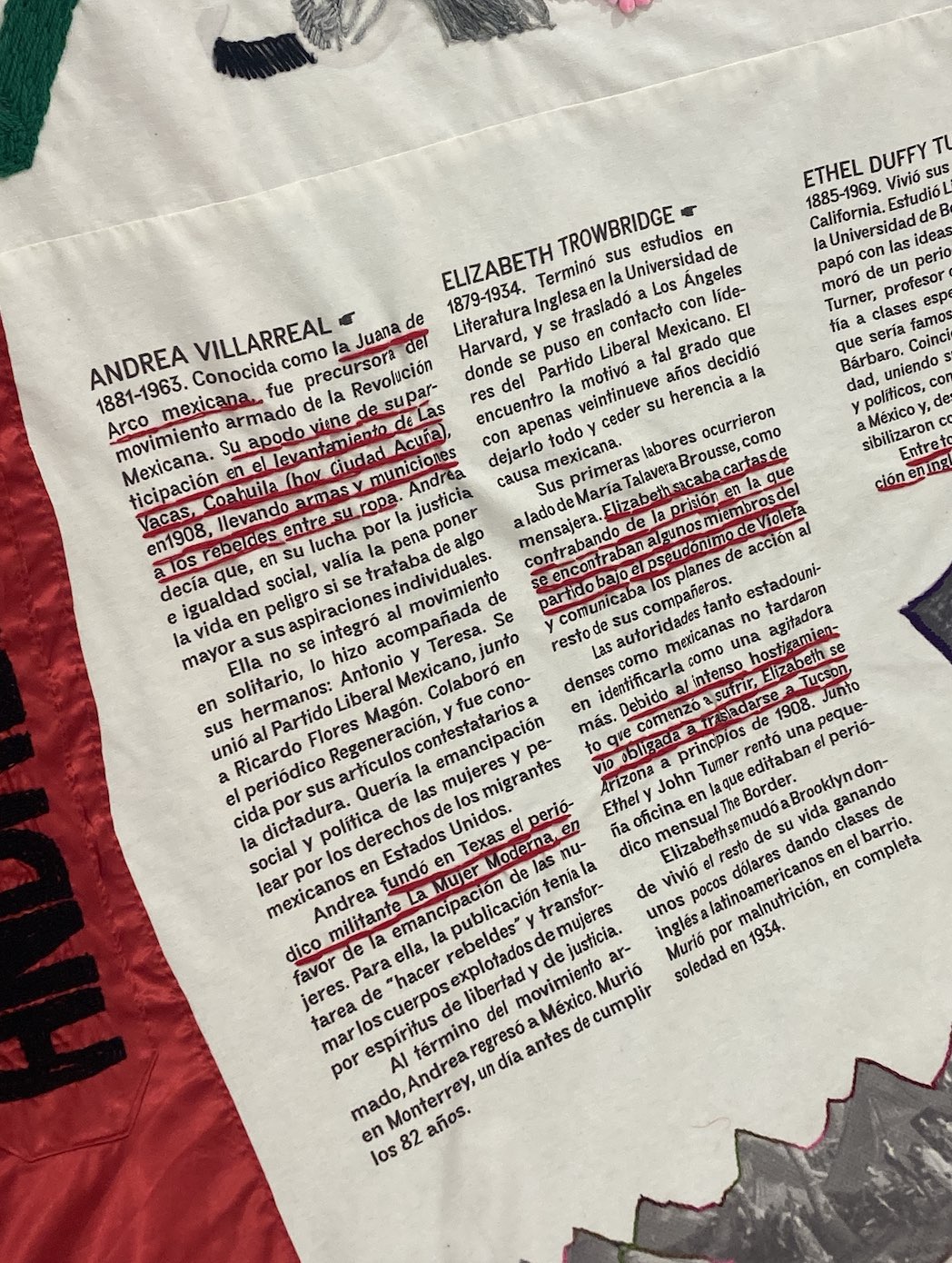

An example would be the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, which, as referenced in the curating material, is a self-organized group made up of mothers, grandmothers, and sisters, who since 1976 have taken to the streets in order to claim the lives of those thousands forcibly disappeared by the State during the Argentine dictatorship. Originally, and as a way of identifying themselves, they have used white headscarves as symbols of their status as homemakers, a strategy also used to make themselves visible and thus avoid being arrested. Another example is seen in Falda dinamita [Dynamite Skirt], by the artist Eunice Adorno, who uses the image of the home-refuge in order to erect a tribute to some thinkers and militants who participated in revolutionary conflicts. When Adorno takes up the figure of the home, aiming to speak about these women’s political radicalism with a basis in such practices as embroidery, she poetically reinforces the idea that it is possible to activate from rest and to rest from activation. On the embroidered piece we see narrated the case of Andrea Villarreal (1881-1963), forerunner of the Mexican Revolution, who participated indirectly but routinely, carrying arms and ammunition within her clothes to the rebels.

Anecdotes such as this recall what Silvia Federici calls “the marginality of the housewife to revolutionary struggle,”1 where the separatism of class struggle selects certain subjects as revolutionary candidates while others are condemned to mere roles of caring support. The same occurs in the division between salaried and unemployed—the activated and the “resting”—which in turn serves to measure an individual’s productivity. Being productive under the system of capitalist domination requires obtaining a salary, a fact that automatically delegates unpaid domestic work to the category of “unproductive."

Therefore, the knowledge acquired throughout this period of “unproductivity” is instantly discarded or devalued. Such activities as cooking, embroidery, and sewing are labeled as docile or secondary, owing to their lack of “professionalization.” Even when transferred to fields of production, they hardly escape those labels. However, during the Industrial Revolution, when labor was freed from the constraints of specialization and the need for physical strength2—conditions supposedly exclusive to men—and women were introduced to textile factories, a change occurred by which they could finally become political and autonomous subjects through work.

Fall of the Manufacture, by the artist Marge Monko, is a photo series portraying the famous abandoned textile factory of Kreenholm, located in Narva, Estonia. In the images we see murals and monuments erected in the facilities of this huge industrial complex, showing the presence and power of its female workers. The treatment given to the image of women in these constructions is far from the passive or voyeuristic representation associated with the “muse.” On the contrary, these are women who are strong, determined, and ready to fight for capital. But the protection offered by industrialization and capitalist development as emancipatory forces that could end the division of labor—in which gender differences would lose all “social importance” thanks to the working class3—failed to manifest. The factory’s state of abandon reinforces the idea of one more unkept promise.

In contrast with the determination revealed by these Soviet monuments, Untitled by Chantal Peñalosa deals with stillness: with waiting as a feminized activity. The work is inspired by the character of Penelope from The Odyssey, who waited 20 years for her husband’s return to Ithaca, thus symbolizing conjugal fidelity. During this period, Penelope wove a shroud that, if completed, would mean the death of King Laertes, which in turn led her to undo the work at night. This story evidences not only the importance of the process, but also of its completion.

Repetition, patterns, threadings, drawing and inserting thread, cutting, undoing and redoing: all establish a rhythm that in its processuality encourages a state of self-reflection and, even, of healing. This intention is evident in the piece Mujeres bordando junto al Lago Atitlán [Women Embroidering by Lake Atitlán], by Teresa Margolles, a video showing the interactions and conversations among some women as they collectively embroider on a bloody cloth that had covered a corpse. Each embroidered motif contains a piece of information, an affection or a complaint that, when stamped on the fabric, contributes to the commemoration of the victims of violence. In turn, the action works as a therapeutic way of assimilating and overcoming trauma. Tying the last thread means suturing the wound in order to make way for healing.

Translated to English by Byron Davies

Notes

1 Silvia Federici, Patriarchy of the Wage: Notes on Marx, Gender and Feminism (Oakland: PM Press, 2021), p. 9.

2 Ibid. pp. 34-35.

3 Ibid. p. 35.

Published on Oct 7 2021